Steps Towards a Reformed Financial Criminal Law in Hungary

With Hungary’s accession to the European Union, the national and European budgets got into considerably closer contact with each other (Polt, 2019a, 139.). On the other hand, we should also see and note that after the accession, the practice of budget fraud related to acquisitions within the EU has evolved. These crimes included various VAT-related frauds such as accepting pro forma invoices related to domestic sales activities and other economic activities related to acquisitions and sales within the Community (Balláné Szentpáli, 2020, 67.). In the second part of our series on budget fraud in Hungary, we focus on the effective Hungarian regulation.

With Hungary’s accession to the European Union, the national and European budgets got into considerably closer contact with each other (Polt, 2019a, 139.). On the other hand, we should also see and note that after the accession, the practice of budget fraud related to acquisitions within the EU has evolved. These crimes included various VAT-related frauds such as accepting pro forma invoices related to domestic sales activities and other economic activities related to acquisitions and sales within the Community (Balláné Szentpáli, 2020, 67.). In the second part of our series on budget fraud in Hungary, we focus on the effective Hungarian regulation.

The New Concept for the Complex Protection of the Budget

Special mention needs to be made of the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon in 2009, which can be regarded as an important milestone in the history of the protection of the financial interests of the EU since it empowered the European Union with a supranational legislative competence in the field in question (Jacsó & Udvarhelyi, 2018, 329., Miskolczi, 2019, 162–163.). This legislative competence is regulated in Article 325(4) TFEU, according to which, ,,(...)the European Parliament and the Council, acting in accordance with the ordinary legislative procedure, after consulting the Court of Auditors, shall adopt the necessary measures in the fields of the prevention of and fight against fraud affecting the financial interests of the Union with a view to affording effective and equivalent protection in the Member States and in all the Union's institutions, bodies, offices and agencies”. These provisions of the Treaty enable the EU to adopt directly applicable, supranational criminal law norms in the form of regulations in this field. However, there are scholars and Member States, who and which do not accept such a competence (Farkas & Jacsó & Udvarhelyi, 2019, 91.).

Over time, the aforementioned, disputed solution was terminated and the fraud-related crimes (tax fraud, employment-related tax fraud, excise violation, illegal importation, VAT fraud, unlawful acquisition of economic advantage, violation of the financial interest of the European Communities) were integrated into one legal definition by Act LXIII of 2011 (Jacsó & Udvarhelyi, 2019, 128.), as an important step within the framework of the reform of the financial criminal law in Hungary. The new ’terminus technicus’ of this integrated legal definition was budget fraud. The reason behind this was to eliminate the duality of several, special fraud-based neighbouring criminal offences to be found in the former Criminal Code (Act IV of 1978), which aimed at damaging the budget, and thereby to avoid discrimination among them (Madai, 2017, 274.).

From the 1st January 2012, the new concept has been introduced, which – similarly to the Directive (EU) 2017/1371, also known as the PIF Directive, which replaced the PIF Convention (for details see a previous blog post of the author) after five years of negotiation, as a part of the Commission’s overall strategy to strengthen the protection of the Union’s financial interests (Juszczak & Sason, 2017, 80.) – is characterised by the unified regulation of the revenue and the expenditure side of the budget. It should be noted that according to Art. 1(1)(a) of the PIF Directive, the concept of „Union’s financial interests” covers all revenues, expenditure, and assets covered by, acquired through, or due to a) the Union budget; b) the budgets of the Union institutions, bodies, offices, and agencies established under the Treaties or budgets directly or indirectly managed and monitored by them (Madai, 2019, 132., Miskolczi, 2013, 10.).

Therefore, the legal definition of budget crime was created as a result of consolidating nine crimes. On the revenue side, tax fraud, employment-related tax, excise violation, illegal importation, VAT fraud, crime affecting the financial interest of the EU, and any other forms of fraud that affect or cause damages to the budget are included in this legal definition. On the expenditure side, the new criminal offence unites the former definition of the unlawful acquisition of economic advantage, the crime affecting the financial interests of the EU, and all the forms of fraud that violate or cause damage to the budget (Polt, 2019a, 140.).

The Effective Hungarian Regulation

The legislator used the abovementioned approach of regulation without any essential changes, the effective Criminal Code (Act C of 2012) essentially took over the provisions of the former Criminal Code with some minor modifications. The result of this consolidation is expressed by the legal definition of budget fraud punishable under Section 396 of the CC. Thus, this Section punishes fraudulent conduct exercised in respect of both the payment obligations and any of the funds originating from any of the budgets listed in the explanatory note specified in Subsection (9) of the criminal offence. Both the revenue and the expenditure side of the EU budget are covered by budget fraud based on the legal definition (Miskolczi, 2014, 3., Miskolczi, 2016, 1323.). Given the latter, the effective regulation protects not only the budget which is managed by the European Union or by the other Member States but also the budget of any other foreign states (Elek, 2018, 238.).

It should be noted that new punishable conduct was introduced into the present legal definition, which is “making a false statement” in connection with budget payment obligation or with any funds paid or payable from the budget. With this provision, the legislator wanted to emphasise that the misleading conduct during the tax return or reporting obligation in electronic form is also covered by this criminal offence (Miskolczi, 2018a, 119.).

Moreover, concerning the common protected legal interest, all offences against the budget are regulated in a separate chapter (Chapter XXXIX under the title ”Criminal offences against public finances”) which contains four criminal offences:

(1) Fraud relating to social security, social and other welfare benefits (Section 395 of the CC)

(2) Budget fraud (Section 396 of the CC)

(3) Omission of oversight or supervisory responsibilities in connection with budget fraud (Section 397 of the CC)

(4) Conspiracy to commit excise violation (Section 398 of the CC)

The new legal definition of budget fraud eliminated the initial problems (Udvarhelyi, 2014, 188.), terminated the differences between the protection of the national and the EU budgets, the issues of cumulation generated by the previous legal definition, and it formulated the criminal conducts abstract enough to include all conducts causing damage to the budget, and simultaneously, it stays in compliance with the wording of the PIF Convention – and the wording of the aforementioned PIF Directive – and by now the legal definition of budget fraud became a well-functioning, efficient instrument for the legal practitioners (Miskolczi, 2018b, 289.).

In the respect of the PIF Directive, it is important to note that it, inter alia, provides for a common definition of fraud and other criminal offences affecting the EU’s financial interests and also for certain types and levels of sanctions when the criminal offences are defined in this Directive have been committed. The Directive is also important for the work of the European Public Prosecutor’s Office (hereinafter: EPPO). The Directive and EPPO are fully interlinked and have to be considered together as key elements of the comprehensive approach towards a stronger protection of the Union budget. The catalogue of criminal offences defined in Arts. 3 and 4 of the Directive determine the material competence of the EPPO under Regulation (EU) 2017/1939. The EPPO is not applied to all Member States; it is established in the form of enhanced cooperation. However, for the unified protection of the financial interests of the European Union, it is helpful to agree with the non-EPPO Member States and the EPPO Member States to develop efficient and active cooperation (see Farkas, 2019, 83.).

Statistical Trends

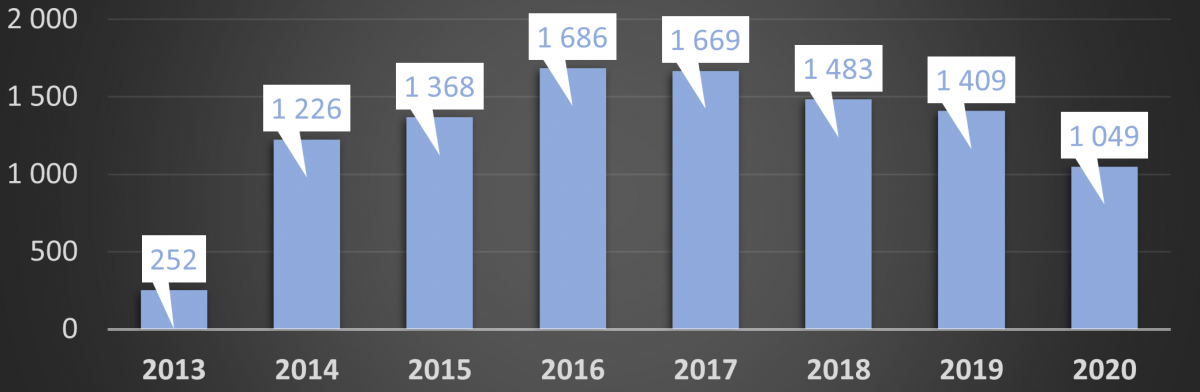

We can point out firstly that budget fraud accounts for nearly two-thirds of economic crimes committed in Hungary. Concerning budget fraud, since the entry into force of the new CC, the authorities registered 252 cases in 2013, 1226 cases in 2014, and this figure has grown to 1686 by 2016; since then, we are witnessing a dramatic decrease which has led to 1049 cases in 2020. Nonetheless, it should be noted that this decrease is significantly minor than the one we have recently experienced in the number of registered criminal offences in total.

Registered budget fraud (2013–2020), source: Unified Criminal Statistics of the Investigation Authorities and the Prosecution Service

Registered criminal offences (2013–2020), source: Unified Criminal Statistics of the Investigation Authorities and the Prosecution Service

This situation is even more interesting if we take into account that regarding the financial loss caused by economic crimes, budget fraud represents 90% of economic crimes and is accompanied by a very low rate of return, approximately 10% (Horváth, 2019, 175.).

Closing Remarks

It is important to bear in mind that we are faced with a complex area of law where cooperation and joined-up thinking among different fields of expertise are essential for an effective investigation of a case. The relationship between tax administration and criminal proceedings is very close since budget fraud also exhausts commonly the elements of tax infringement at the same time (see also Molnár, 2011.). This raises several questions and problems (see Elek, 2016, Elek, 2019a), of which only the mutually exclusive effects of the procedures, the applicability of sanctions, and the applicability of each piece of evidence are exemplary (Horváth, 2019, 148.).

In summary, it can be definitively concluded that it is extremely difficult to fight against budget fraud and therefore crime prevention may be necessary to fight off the number of criminal offences as well as diverting law enforcement agencies into the right direction regarding ongoing procedures (Balláné Szentpáli, 2020, 67.). For all these reasons, provisions accelerating proceedings – which constitute a novelty under the new Criminal Procedure Code (Act XC of 2017, which entered into force on 1 July 2018) – in the context of budget fraud go beyond the framework of domestic regulations, as it is not irrelevant how much time will be spent on adjudicating conduct which infringes the financial interests of the EU. Thus these possibilities in the field of criminal proceedings serve not only the interests of Hungarian law enforcement but also the interests of the EU (Szentpáli, 2019, 121., Tóth, 2011, 438., see also Polt, 2019b, 14.).

Although it is also related partially to criminal procedural law, it is important for our topic that it is more and more apparent in cases of criminal proceedings initiated due to the budget fraud – which manifest the protection of the financial interest of the EU – that by now the European criminal law became a reality, in which – in addition to the protection of common interests – the legal practitioners cannot omit the legal harmonisation of criminal procedural law and the consideration of procedures conducted in the other Member States (Elek, 2019b, 234.).

* * *

For a list of references, click HERE.

Author: dr. Petra Ágnes Kanyuk, Ph.D. Student at the Géza Marton Doctoral School of Legal Studies of the University of Debrecen, Department of Criminal Law and Criminology

The study was made under the scope of the Ministry of Justice’s program on strengthening the quality of legal education.

Source of the image used:

https://www.rai-see.org/fraud-suspicions-of-over-eur-231-mln-with-eu-funds-in-romania/ [accessed April 8, 2021]