Key highlights of a study: The situation of women in public transport

The characteristics of people's daily transport routines are different, as they differ according to the size of the settlement, various social and demographic characteristics, different travel destinations and even the season and time of day. [[i]]

In our empirical survey, we chose to examine one of the most significant influencing factors, namely the gender aspect in Debrecen and its immediate vicinity. According to a 2019 OECD report, the needs of men and women in public transport are different. The latter prefer to use public transport more than the opposite sex, yet their needs are taken into account less when making transport decisions. [[ii]]

Introduction

Access to reliable, safe and affordable transport is essential for the proper social and economic participation of people and it is an integral part of human well-being. Men and women generally have different preferences for transport, but transport policies do not take into account gender differences in transport. [[iii]] However, ignoring women’s transport and mobility preferences, among other things, limits their economic and social participation. For example, a study found a negative correlation between commuting time and women’s participation in work. [[iv]]

If commuting time increases by one minute in metropolitan areas, it will result in a reduction in the workforce of women of around 0.3 percentage points. In addition, women do not simply commute between work and home, but additional journeys related to household responsibilities, such as shopping and caring for children and the elderly, play a large part in their lives. It can also be stated that women, on average, travel less frequently and for shorter distances and are more willing to reduce car use than men. [[v]]

It can therefore be concluded that when public transport is available, women prefer it. On the other hand, shorter and more diverse travel destinations can make women an attractive target for public transport. According to a 2018 study covering eight European and Asian cities, women travel, on average, less than men, use more public transport and travel more off-peak. [[vi]] However, as women’s travel habits are more complex, they tend to prefer more flexible modes, but at the same time public transport modes are more attractive to them. If decision-makers offered better alternatives, women would be more likely to choose to travel by car and prefer public transport. If decision-makers want to encourage flexible and sustainable urban development, in which the development of transport dominates, policies that take greater account of women's preferences must be designed and implemented. Indeed, although women prefer to use public transport, most cities do not have transport programs that focus on improving the user experience for this group, especially with regard to their travel goals, their sense of security and their off-peak travel time. Transport safety is a key factor in shaping women’s mobility preferences and choices, especially in urban areas where more women use public transport. For example, a study found that the vast majority of women worldwide do not feel safe in public transportation and have previously experienced some form of physical or verbal harassment in public. [[vii]]

If women do not feel safe, they often prefer to take a car or use a taxi. It can be concluded that if decision-makers want to increase their use of public transport, they need to improve the safety of their services and the travel experience.

In order to take the situation of women into account in public transport as much as possible, it is necessary to assess their needs and involve them more closely in decision-making. Involving this group can improve legitimacy, participation, and ultimately the quality of service. After all, it is often assumed that different genders benefit equally from infrastructure development, although they do not recognize the potential different effects on women and men. For example, an urban development project that also affects transport should pay more attention to the quality of public lighting, safe public spaces and public transport.

We empirically measured the relationship of women with public transport. For the first time in the research, five in-depth interviews were conducted with two mothers aged 25-35 raising young children and three respondents aged 45-55 raising older children. After summarizing the responses and drawing conclusions, we surveyed the needs of women in public transport anonymously using an online questionnaire, which resulted in 419 (86.7% female) responses.

In compiling the questions of the questionnaire and the interview, in addition to the previous experience of the Debrecen Regional Transport Association (DERKE), the results of international research also helped to achieve the goals. For example, according to a survey in the UK and Jakarta, women do not feel safe on public transport. [[viii]]

The situation has only been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has significantly changed daily mobility habits worldwide as self-owned cars and bicycles have become the most popular means of transportation, while the use of public transport and travel sharing services has taken a back seat. [[ix]]

In several countries, public transport is being pursued with a stronger focus on women, such as the creation of wider sidewalks in Vienna to help mothers with small children, improvements to public lighting, and access to streets and public transport. [[x]]

The solution in New Delhi, where women can use public transport free of charge, is a highlight, a step that is expected not only to reduce air pollution but also to increase women's safety and security. In support of the latter objective, cameras (approximately 150,000) have been installed in several public areas. Tokyo and Osaka went so far as to introduce segregated transportation. Women, people with disabilities, and children and their caregivers can travel on specially designated cars on the railways (similar solutions exist in Mexico City, Dubai, Cairo, and Tehran).

Research results

We tried to narrow down the empirical research to the area of Debrecen.

The interview

Each of the five interviewees regularly uses public transport during their travels. However, those who have a car use public transport specifically only for some strong extra motivation - such as environmental protection, raising children -. Interestingly, however, costs do not play a significant role for the majority, and cycling is only an option for one of the young mothers, while others are afraid of urban cycling.

The terms “crowd” and “waiting” first came to mind for all respondents about public transport, as it is (especially the latter) very burdensome for young children. The lack of stops and vehicles and the lack of cleanliness were a real problem for older mothers.

According to the interviewees' subjective opinion, there is basically no difference in the expectations of women and men towards public transport and they have only identified it as an indispensable way to reach their destination, while they also questioned the importance of the lack of travel etiquette. In their view, there are also problems with the transfer of seats and the courtesy of fellow passengers.

It is important to point out that mothers with small children often use public transport services outside peak hours, especially until the child is in public education. Stakeholders in this age group unanimously identified vehicles arriving and departing too early as the main problem, as they believe that arriving at the stop several minutes before the scheduled departure of the flight does not reach what is possible with a child and all accessories (stroller, changing bag, shopping). together is particularly problematic. This results in another expectation coupled with children’s impatience. However, it should be noted that several positive examples have been offered concerning the attitude of drivers.

Questionnaire

Based on the responses, the questionnaire was compiled into three main sections. Thus, in the first part, we tried to explore social and demographic issues and travel habits, and then tried to get a complete picture of the factors that help and hinder the use of public transport. Finally, we also gave room for open proposals.

For most respondents, work and shopping are their primary destinations. The most commonly used mode of transport is public transport (78.5% use daily), while cycling and scooter transport are the most rejected. It can be stated that the proportion of public transport users is higher in families with older children.

Based on these results and interviews, it is likely that women will “return” to use public transportation as soon as their child gets older, but this is not guaranteed at all. Although we cannot, of course, predict this, perhaps the change in residence over time may have an impact on the process. According to the questionnaire survey, it is worrying from the point of view of public transport that the use of public transport is extremely low among women living in a single-family zone with children under the age of two. This group has already clearly switched to passenger cars and further outbound population movements are expected in these areas, including a reduction in the use of public transport.

Based on these results and interviews, it is likely that women will “return” to use public transportation as soon as their child gets older, but this is not guaranteed at all. Although we cannot, of course, predict this, perhaps the change in residence over time may have an impact on the process. According to the questionnaire survey, it is worrying from the point of view of public transport that the use of public transport is extremely low among women living in a single-family zone with children under the age of two. This group has already clearly switched to passenger cars and further outbound population movements are expected in these areas, including a reduction in the use of public transport.

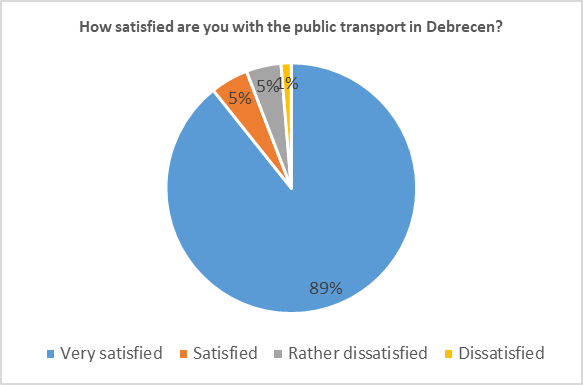

As for the subjective opinion of the respondents, almost half of the respondents are satisfied with the public transport services. Satisfaction is higher than average for those living in the city center, while the opposite trend is seen for those living in the suburbs.

The results show that women 's travel among those raising children under the age of two usually does not fall during peak periods, which is no longer the case for women whose children are over this age. Based on these, we can see a significant difference in terms of our proposals, which also confirms the everyday experience and the results of the in-depth interview survey: parents of young children, who typically travel with prams or baby carriers, tend to travel in much higher proportions during less saturated periods, while the peak period is again dominant for parents with children that are already walking independently and typically no longer using prams.

One of our questions was intended to assess the burden of waiting. Waiting is mostly a problem for those with small children, including mothers raising children under the age of two. The distribution of responses to the question by those raising older children has already given below-average importance to waiting as an annoying factor.

One of our questions was intended to assess the burden of waiting. Waiting is mostly a problem for those with small children, including mothers raising children under the age of two. The distribution of responses to the question by those raising older children has already given below-average importance to waiting as an annoying factor.

The assessment of travel etiquette is not positive, although it should be noted here that the the extreme negative value allowed in the questionnaire was not the most commonly marked one, and in response to an open question, several people explained that this could not be blamed on the service provider at all. All this is supported by the fact that the lack of courtesy is also experienced by those who are otherwise satisfied with the service. In this question, by the way, we have not discovered a pattern related to the age of the child, moreover, contrary to our expectations, the younger age group is less tolerant of rude behavior, which may be important from a communication point of view.

The statement that mothers with small children always have a seat on the vehicles divides respondents. Although many share this view, there is a slight majority of respondents who disagree with this. Those raising a young child see the situation as bad more commonly than the values of those raising a child over the age of ten or the entire sample.

According to a slight majority of respondents (51%), the driver does not have to warn the traveling public about giving up their seat. Interestingly, young people in particular disagreed with this statement. Based on the etiquette results above, we can say that they may have interpreted the question that it is a pity that the suggestion arises at all.

We agree with the statement that children enjoy travelling on public transport vehicles, in line with the interviews, both on the basis of the whole population and the individual subsamples.

Based on the answers we received to our question about extraordinary incidents and the availability of information about them, we can state that the absence of information is not age-dependent. With this, we have to reject the hypothesis that the younger age group would receive more or earlier information on the Internet (news sites, applications, etc.). (Answers to open-ended questions can be found in the Research Report. [[xi]])

Summary: Suggestions

The results of our survey can be summarized as follows:

Waiting with a small child is especially stressful for both the child and the parent. With the youngest children, a higher proportion of trips take place outside peak periods. For this reason, it may be important to prevent public transport vehicles from running earlier than scheduled, to “decorate” the passenger waiting area, to display entertaining visual elements, and to provide much more extensive and effective passenger information (about disruptions in service, delays, accidents, etc.). We consider it very important to provide passengers with up-to-date timetable data and information on the fulfilment of the timetable as soon as possible. The real-time passenger information software side has evolved a lot in the last decade, as there are no longer any technical barriers to the immediate delivery of information. Keeping pace with the technical possibilities, however, it is necessary to establish a regulatory framework for real-time passenger information on the service provider side so that front-line staff are aware in all circumstances of when and how the information should be provided.

Reserved seats for travellers with small children may be required to enhance the travel experience. In addition, the extension of the use of the disabled stop button to indicate someone wishing to alight with a stroller and the clear communication of this function on the vehicle should be considered.

Finally, specific training for drivers should be provided concerning issues such as the avoidance of using loud sound signals too early when closing the doors of the vehicle.

Authors: Mihály Dombi PhD, assistant professor, DE GTK Institute of Economics and Dr. Dóra Lovas, Assistant Lecturer at the Faculty of Law of the University of Debrecen; Research fellow at MTA–DE Public Service Research Group and Zoltán Jónás, President of the Debrecen Regional Transport Association.

The study was made under the scope of the EFOP-3.6.1.-16-2016-00022 "Debrecen Venture Catapult Program".

[[i]] https://www.oecd.org/gov/gender-mainstreaming/gender-equality-and-sustainable-infrastructure-7-march-2019.pdf (2022.06.15.)

[[ii]] Részletesebben: https://www.derke.hu/sites/default/files/DERKE_kutatasi_jelentes_noi_utasok_2022.pdf

[[iii]] Sharon Sarmiento: Household, Gender, and Travel, Baltimore, 1996. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ohim/womens/chap3.pdf (2022.06.15.)

[[iv]] Black, Dan and Kolesnikova, Natalia and Taylor, Lowell J., Why Do So Few Women Work in New York (And So Many in Minneapolis)? Labor Supply of Married Women across U.S. Cities (March 1, 2012). FRB of St. Louis Working Paper No. 2007-043H. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1129982 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1129982 (2022.06.15.)

[[v]] Patrick Moriarty and Damon Honnery: Determinants of urban travel in Australia. 28 th Australasian Transport Research Forum, 2005. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233779196_Determinants_of_urban_travel_in_Australia (2022.06.15.)

[[vi]] Wei-Shiuen Ng and Ashley Acker (2018), Understanding Urban Travel Behaviour by Gender for Efficient and Equitable Transport Policies, International Transport Forum Discussion Paper No. 2018- 01, https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/docs/urban-travel-behaviour-gender.pdf (2022.06.15.)

[[viii]] https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/docs/urban-travel-behaviour-gender.pdf (Letöltés dátuma: 2022.06.15.)

[[ix]] Continental Mobility Study (2020), https://cdn.continental.com/fileadmin/__imported/sites/corporate/_international/german/hubpages/10_20presse/studien_und_publikationen/mobiliteatsstudien/2020/mobistud2020_welle_2/20210623-continental_mobility_study_wave2.pdf (2022.06.15.)

[[xi]] https://www.derke.hu/sites/default/files/DERKE_kutatasi_jelentes_noi_utasok_2022.pdf (2022.06.15.)